future: restoration

“Education is what hurt us but I believe education is what will heal us”

Jeff Horvath, principal of Manyhorses High School, Tsuut’ina First Nation, near Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

On a similar timeline as awareness of Indigenous issues has been growing, so too has awareness of the highly damaging relationship humanity has with our planet. There is now general consensus that our environment is beginning to change in ways that poses existential threats to humanity and many other forms of life, and that we are major contributors. There is also greater awareness about the highly dysfunctional relationships that exist in our societies – from the interpersonal, the familial, and to the global. There has also been significant research and exploration into potential solutions, from brain research, psychological, geopolitical, pedagogical, to school facility design. There are significant parallels between progressive advances in mainstream society's approaches to learning and those practiced and lived in many Indigenous cultures.

A central theme for this is restoration - of our relationships with each other and with our planet. As Indigenous practices are re-emerging and becoming better known, considered, and even accepted by non-Indigenous people and systems, there is increasing awareness of what everyone can learn from Indigenous relationships amongst people and with the environment. Common to both systems of societal justice and environmental iteration are restorative practices.

Humanity's dominant systems are based on a worldview of humanity's separateness from, dominion over, and wonton destruction of the environment. There are other worldviews, including one that is central to many Indigenous peoples, where humanity is considered being a part of, dependent on, integral, and perhaps even beneficial to the environment. One of these is the basis to societies that were the most - and arguably the only - truly longlasting and sustainable ones we have known. The other worldview has brought us to the verge of destruction.

This is not ground-breaking news, and even Western science has begun to recognize the credibility and value of Indigenous learnings and practices.

In 2015 the University of Salford released a study entitled Clever Classrooms, created by researchers led by Peter Barrett (and funded by an architectural firm now known as Arcadis). This study - for the very first time - documented the impact on academic test results of such environmental characteristics in schools as naturalness, natural light, fresh air, and appropriate stimulation. The impacts on test results were significantly positive. Put another way, about eight years ago, western science first documented what has been known and practiced by Indigenous peoples for millennia.

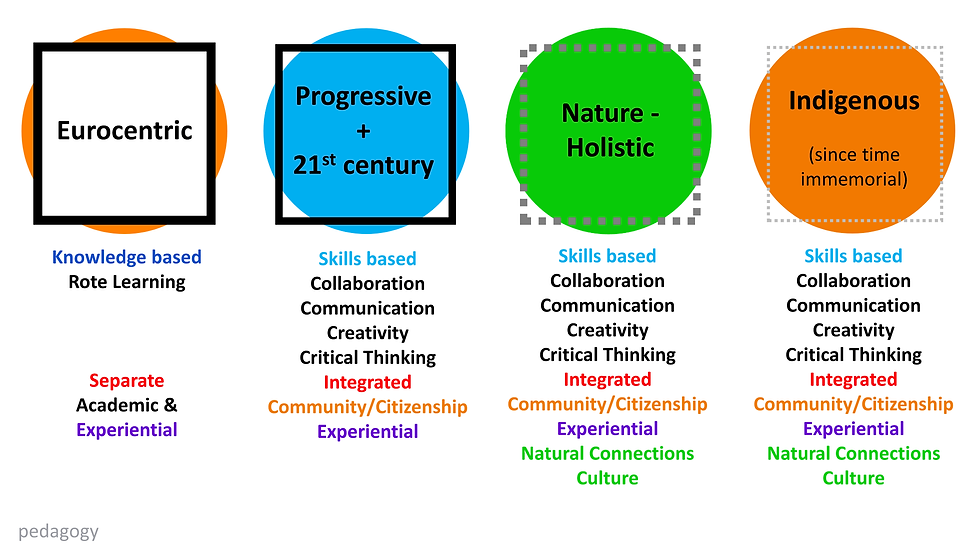

Pedagogical Models:

The image below is a simplistic overview of the main tenets of the most widespread instructional models, or pedagogy, that have emerged since the late 19th Century. In the diagram below, the square boxes represent the walls of the classroom or school building. The circles indicate the context. The circles and the squares in the diagram are very intentional – as we are seemingly learning more every day, we round Eurocentric humans are actually rebelling against being constrained within simple boxes. We are learning that in order to thrive, our round bodies need to be outside of the square boxes we build.

The Eurocentric model - sometimes called the traditional or Factory Model - was developed from the Prussian Model brought to North America in the late 19th Century by Horace Mann. It focused on creating an efficient system for educating the most students as possible for the least effort, with a goal to providing knowledge needed for emerging industrializing societies. It was largely knowledge-based with separation between academic and experiential or hand-on learning, such as trades for boys and home economics for girls. This was the dominant model throughout the 20th Century and continues today as a dominant pedagogy in much of the world. Another term for the physical and pedagogical design, which is typified by multiple identical classrooms aligned on either side of a long hallway (or double-loaded corridor), and with students sitting in straight rows facing a teacher learning by direct instruction, is the Factory Model. This has been termed “cells with bells”; indeed, much of the planning was derived from, or at least developed in tandem with, designs for prisons, where the need for efficiency and control is paramount. The knowledge is broken into separate periods of time, and with older students, each classroom or teacher is dedicated to a single subject. The teachers and their subject-focused classrooms may be organized into departments and disciplines. Learning is siloed, with little crossover between subjects or projects. Especially with academic subjects - those which are not hands-on or project-based such as trades, art, or science - the knowledge transfer is uni-directional. This pedagogy has also been termed “sage on the stage”.

In this model, the boxes quite closely reflect the shape of the typical learning environment, including many with little to no exposure or connection to the outdoors. Each space is isolated and a tightly controlled environment unto itself.

The 21st Century Model - which has early 20th century roots in the Progressive Model, including the Montessori Method, experienced only intermittent popularity until re-emerging as “21st Century learning”. It is skills-based and includes integration of academic and experiential learning, including project-based, problem-based, and other interdisciplinary approaches. It is noted for tenets which are commonly styled “the 4-C’s”: collaboration, communication, creativity, and critical thinking. Other “C’s” are frequently included, such as community and citizenship. This has also been called “Next Generation Learning”. Learning spaces may be organized into neighborhoods or pods, frequently with shared access to flexible spaces, labs, or specialized learning spaces. For younger students, each neighborhood may contain a cohort of multiple grades, so that students stay amongst familiar teachers, spaces, and classmates over multiple years. For older students, classrooms in each neighborhood may each be dedicated to different subjects, so while students may move amongst spaces, they remain mostly within the same area and with the same cohort of students. This model supports project and problem-based learning, mentoring amongst different age students, differentiated and personalized learning, team-teaching, and similar other interdisciplinary and collaborative pedagogies. This configuration also supports different school organizational models, from departmental, academy, to small schools / schools-within-a-school.

This model incorporates outdoor learning spaces, frequently highly controlled spaces which may be best described as outdoor classrooms. A pioneering example of this is the Crow Island School, designed in the 1930’s and located in the mostly-White, affluent suburban community of Winnetka, IL.

The Nature-Holistic Model (my term, offered here until another gains acceptance), reflects emerging trends seen in many areas. The Holistic Model, incorporating holism, is essentially the 21st century model but with addition of spirituality and social-emotional components. The definition is varied and evolving. This has most recently begun to focus more on specific approaches such as trauma informed design, equity, inclusion, and belonging. The Nature-Holistic Model builds upon these to incorporate an emphasis on culture and natural connections.

In this model, the walls begin to break down, through transparency and openings allowing movement from indoors to outdoors.

The Indigenous Model - whose tenets are commonly found in many Indigenous cultures in North America, is on the face of it no different from the previous model. (There is of course no singular model that applies to all Indigenous cultures or practices, which as highly diverse, but there are strong commonalities among many. No doubt others will emerge into general awareness).

In this model, the walls are all but gone; it’s not that Indigenous schools don’t have indoor spaces, or even traditional classrooms, but that the outdoor experience is incorporated throughout the curriculum. This recognizes the outdoor learning experiences of students during and after school hours. For some schools, outdoor learning is the dominant form, ranging from part of a given day or to some schools in northern Canada where students the majority of their academic year being continuously outdoors over many consecutive days and weeks.

The Indigenous educational model, illustrated below, is holistic and focused on the whole child, both key tenets of 21st Century and Next Gen+ Learning. The holistic approach involves not just placing the learner at the center of the learning experience, but also reflects, instructs, and demonstrates about the learners’ place in their environment – social and natural, both at and away from school. From the perspective of the “whole child approach”, six main areas emerge, in both Indigenous and mainstream models:

-

Pedagogy: experiential, interdisciplinary, project-based and problem-based, critical thinking.

-

Curriculum: includes (but not limited to) science, art, math, language, history, music, activities.

-

Physical health: fresh air, healthy food, physical activity.

-

Social emotional health: focus, de-stress, trauma, empathy.

-

Culture: history, community, connectedness.

For the Indigenous Model (above), there are at least three additional aspects connecting each of these:

-

Spirituality

-

Family

-

Nature

PEDAGOGICAL ELEMENTS

The Indigenous Model of learning is highly focused on relationships: interpersonal, social, and nature-based. The following are notable examples of how the Indigenous Model differs from the mainstream models.

Interconnected: “I am because we are”, or “humanity towards others”, is at the core of Ubuntu philosophy. It is integral to many societies, with different descriptors and practices. But it is not perfunctory or purely historical, such as John Donne’s 17th century line “no man is an island”.

An example of this worldview – which is clearly not reflective of a mainstream western mindset - was described by Jared Qwustenuzum Williams, a First Nations educator on Vancouver Island, in a 2023 social media post:

"Any knowledge I hold, any wisdom I share, any of my language videos or stories, those are not mine. You may watch these videos and you see me, but this information is from … all of the ancestors and the direct work I’ve had with the elders. Like my late grandmother, Qwustanulwut. Or my auntie, t’awawiyu’. Or my really good friend Luschim. Or Hwiemtun. The list goes on and on and on, and I would have nothing if I didn’t have any of them. And so what I share is not mine in the way that they say we don’t own our names, we wear them. Well, I don’t own this knowledge, I wear it and I’m sharing it with everybody. Because that is how I was raised. You share.”

Storytelling is critical for cultural survival, and not just for societies that did not (or for some, still do not) have written languages that can store libraries of history and knowledge. For many Indigenous societies in North America, written language only came with colonization. As such, any written form of knowledge, including recording in Indigenous languages, was inevitably distorted and limited by outsiders’ understandings, translating abilities, and cultural distortions. In many cases it was not benign neglect or error, but intentional misrepresentations to codify Indigenous people as “less-than” the settlers or to overlay religious dogma and perspectives. In recent years there have been increasing efforts and government initiatives to preserve languages in their original form, including specialized phonetic alphabets that convey particulars of different languages – including generating sounds by using parts of the speakers’ mouth, tongue, and throats not used by the settlers. An example from Africa is the well-known comedian Trevor Noah speaking in his native Xhosa language, whose clicks and throat contortions produce sounds not found in western speech.

The elder in the image below has made it her life's work to instruct others in her community and nation how to speak their traditional language. Much of this is achieved through storytelling.

Beyond the mechanics of the sounds of different languages, meanings are highly culture-based. Kanyen'kéha, the language of the Haudenosaunee or Mohawk people, is verb-based; things are described not just with names, such as “computer”, but with descriptors of their uses. In Cree, the word for “brother” translates as “he who walks through life with me.” This non-DNA-based perspective is a profoundly different worldview to the individual or nuclear-family-based society in which most of us live.

Storytelling frequently incorporates ceremony to enhance and instill information in listerners' and performers' memory. The simple act of verbally conveying information affects the storyteller: they need to learn and remember the information, but actually telling the story fosters retention. This process also fosters empathic interactions between storyteller and the audience. For some cultures, the storytelling starts when two people meet for the first time, such as how Dr. Terri-Lynn Fox introduces herself:

“The protocol for introducing one’s self to other Indigenous people is to provide information about one’s cultural location, so that connection can be made on political, cultural and social grounds and relations established. Oki, niistoo’akoka Aapiihkwikomootakii, Miracle Healing Woman. I am Miracle Healing Woman, as my traditional Siksikaitsitapi name details. My English name is Terri-Lynn Fox. My ancestral land I am connected to is the Siksikaitsitapi, or Blackfoot Confederacy. I have four children and six grandsons; my parents are O’taikimakii ki Ihkitsikam. My maternal grandmother, Poonah, was the daughter of Miikskimm, Mary Derouge (Blackfeet and White heritage), and Tatsiiki’poyi (Joe) Iron, who was the son of Ki’somm, Moon. My maternal grandfather, Mookakin, was adopted by Weaselhead. My paternal grandmother, Pi’akii, was the daughter of Morris Many Fingers and Annie Pace. My paternal grandfather, Tsa’tsii, was the son of Stephen Fox and Cecile Charging Woman.”

Intergenerational mentorship involves all ages participating, where knowledge is passed directly through observation and participation. This may involve diverse activities such as harvesting a crop or constructing a building. Although not unique to Indigenous communities, it is no longer common in other cultures, and highly uncommon in schools where students are strictly separated by age. An example of how this manifests was provided to me by an Indigenous educator. Each person is assigned – or gravitates – towards age-related tasks. What this means is that everyone can see the entire process: what they will be doing as they grow older and what they did when they were younger. Mentoring and sharing of wisdom from community knowledge-keepers is natural; instruction is through demonstration, open observation, and hands-on experience. It is cultural, interdisciplinary, and intergenerational. Expertise is not held by official instructors but by all: family members, neighbors, and elders. Knowledge is shared widely and equitably within the whole community.

Culture impacts many aspects and subject areas within the Indigenous model. Beyond students learning and being taught in the language spoken at home or by their elders – and ancestors – it involves different knowledge bases regarding science, horticulture, and even mathematics and astronomy. It extends beyond Indigenous alternatives to western mythological overlays of the cosmos – Ancient Greek and Roman gods assigned to various patterns of stars. In what is perhaps the greatest contrast to non-Indigenous learning models, for Indigenous people, culture is inseparable from nature.

Interdisciplinary thinking and learning are foundational to many Indigenous cultures. One's place in the world and in society is not siloed or considered separately. Just as nature is an inseparable connection of matter, energy, and information, so top are Indigenous awareness of one's interconnectedness. It is also the embodiment of non-Indigenous holistic approaches in pedagogy.

Food is important in many cultures, but in particular to those who live closes to its source. Most, but not all, Indigenous peoples in North America live outside of large urban centers, many at great distances. Unlike westernized farms, in particular modern large-scale agribusinesses, most Indigenous communities that hunt and fish for significant portions of their food supply. The natural and living resources that are harvested commercially for sale do play an important part in the economies of these communities, but to a large part the food that is caught, hunted, or grown is consumed by people known to those who grow, gather, catch, or hunt this food. This is a continuation of hunter-gatherer and ancient agricultural practices that have sustained communities since time immemorial. It is not unexpected then to find food as not just an integral, but vitally important to communities that live closely to the land – from agricultural and farming communities, remote locations with only distant connections to centers of civilization, and cultures with largely unbroken connections to the land and sea on which they depend for all aspects of life.

Food sources for many Indigenous peoples are not distant and impersonal. Communities have seasonal celebrations honouring migrations of animals important to peoples’ survival, such as the roaming plains bison or the return of the whales. The means of catching, hunting, and growing the food are passed on through generations of families and community elders – as are means of preparing, cooking, serving, and celebrating. Foods not easily found – or not found at all – in urban centers and therefore known only to rural Indigenous communities include muktuk (whale blubber), oolichan (small fish used for oil), wild rice (as a seasonal staple), caribou, or bear. Similarly, plants and herbs known for medicinal qualities are only now being examined and recognized as valuable by western scientists. Where I live, berries found in summer and autumn on roadsides, public parks, nature trails, or even in ornamental gardens are frequently shunned as anything other than ornamental, or mistaken as poisonous; their value as flavourful food, medicine, and dyes in artwork are surprisingly unknown to most who live amongst them, although well known to those of us who have been fortunate to have heard Indigenous teachings.

Emotional and behavioral skills need particular support for Indigenous communities dealing with isolation and disconnection from the opportunities offered by mainstream society, and in particular, with the generational effects of the residential schools systems. Many families are dysfunctional and suffer from problems of dire poverty, parents who received inadequate or even culturally harmful education, substance abuse, suicide, etc. Special programs and specialists in the schools are key to understanding and fostering connections and healthy relationships needed for learning.

Restorative practices are an integral part of many Indigenous cultures. Instead of punishment instilled by a 3rd party, such as a court, restorative practices bring offender and victim – and everyone affected by the offensive act – together to discuss not just the act, but its causes, its impact, and how healing can begin. It’s not about punishment, it’s about restoring and repairing broken relationships. It’s been found to have huge impacts on communities of all kinds and is being introduced in schools, prisons, and other organizations – in part, as a means of countering the school-to-prison pipeline. The greatest effects of the pipeline in Canada are on Indigenous people; in the United States, it is Black people. Restorative Justice Practices have been part of Indigenous justice systems for generations. Although fairly new to settler cultures, they are now being incorporated into the mainstream justice system, such as with special courts in Ontario and Yukon.

Relationships amongst people and with the natural world are seen very differently in many Indigenous cultures than with settler cultures. Over the past year I had two encounters that each offer powerful examples of how different are perspectives of Indigenous and settler cultures.

The first was a video that demonstrated how the depth and power of one’s relationship with nature is formally recognized and celebrated in non-settler cultures. (The images above are from online videos). The Nehiyawak people of northern Canada perform what they call a Walking Out Ceremony. Before a child reaches about one year of age, they are not allowed to walk on the ground until a formal introduction is made. A special ceremony is then held with extended family and community elders that has the parents lead their children outside carrying small tools they will be expected to use when they venture outside – an axe, container for collecting water, bag for herbs, etc. Each, held upright by their parents, are dressed in traditional formal wear and are introduced to a tree and other natural things they will encounter as they venture out on their own in later years. I later learned from colleagues and friends from central and western Africa that similar ceremonies are common there.

The second was social in nature, and although many of us present had lived close to Northwest Indigenous peoples for most of our lives, this event offered fresh new insight for most, if not all, of the non-Indigenous peoples there. (See photo above). At the conclusion of a dedication of a new high school in southern Washington state in 2022, for which I had the privilege of leading the design, there was a performance by the local tribe’s drum band. (Although a public school, local Indigenous people were significant community partners). At the conclusion, the lead Elder, dressed in the traditional formal regalia of her people, spoke:

“During that song, there was a mistake made by one of our drummers. We’re all taught you come ready with your regalia, with your equipment, your drumstick ready. There was a mistake made, so we need to send an apology. Mr. (Superintendent), I am apologizing for the drumstick that fell on the ground. Mr. (tribal member) is our carver, and he did a lot of work for us here, so I want to acknowledge him, and apologize for the drumstick that fell on the floor. We have the architect, that helped with this building, and I want to shake your hand and apologize for the drumstick. This is how we do things in our way.” Each of us was invited up to shake the Elder’s hand and receive their solemn apology, a small gift. It was powerful and humbling, and spoke of deep and sincere respect for others in a way that I had not previously experienced.

Each of us was invited up to shake the Elder’s hand and receive their solemn apology, a small gift. It was powerful and humbling, and spoke of deep and sincere respect for others in a way that I had not previously experienced.

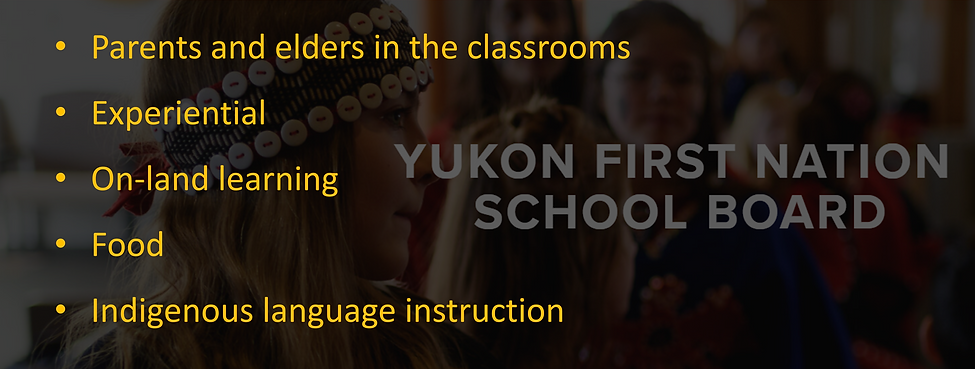

Case Study: Yukon First Nations School Board

In early 2022, a school board was established across Yukon Territory for schools with significant First Nations populations. Yukon occupies the northwestern-most portion of Canada which borders on Alaska, comprising an area larger than all but two US states, yet has a population less than 45,000, of which one quarter are Indigenous (Frist Nations, Metis, and Inuit). Eight schools opted to join to develop Indigenous curricula and programs that are culturally relevant and supportive of students and their communities. Their organization chart places the students at the center, followed by Families, the Land, various levels of institutions, and with all embraced by the Elders and Knowledge Keepers.

DESIGN ELEMENTS

Certain elements of design are of particular importance, and are important differentiators, for Indigenous schools. Some are directly related to the learning program elements described previously/

Winston Churchill observed that “we shape our architecture; thereafter it shapes us”. The building he was referring to was the British House of Commons, whose physical form is the model for the what is known as the Westminster style of government: two groups facing each other, historically separated by a distance of two sword lengths; government and opposition; winners to one side and losers to the other. This configuration both represents and reinforces – even dictates – systemic behavior that is the antithesis of collaboration and consensus. It is argued that it is a strength – it inarguably is the dominant approach throughout much of the world. But it is not the Indigenous way.

Engagement processes needed for an authentic and successful design process begins with developing trust. For Indigenous communities in particular, that can be very difficult when dealing with design teams and “experts” from outside the community, from the dominant culture that continues to inflict harm. Major design projects are by their nature disruptive to the way any community functions, from seemingly straightforward interruptions of daily routines to attend design or review meetings to opening of issues not frequently discussed. For Indigenous communities, this may involve opening wounds that range from generational trauma to recent and familiar to anyone. Trust at many levels has broken down, and establishing a safe place for open communication is key. Sometimes the barriers are linguistic – many Elders in remote communities don’t speak the same language as youth, or outsiders. Other barriers may be cultural – beyond linguistic, the concepts and perspectives don’t always translate easily. For many, these meetings are the first opportunities for people to imagine a better future.

Embracing the community’s ways and relationships can be key; having the designers and project leaders – especially if from outside the community – step back and turn over control of the meetings and questions to those from the community, where they become observers. It is not uncommon for such a process to have Elders open up to their own families in group settings and discuss past events, traditional ways, and future dreams in ways not otherwise shared. Suppressing such ways of thinking and expressing oneself are remnants of what was inflicted on many current Elders by church officials when they were in the residential schools. Engaging the youth not only facilitates intergenerational connection, but also places the learners at the center of determining how their school – the new center of their community – will be. Beyond the engagement process, incorporating youth into the design and construction process – as interns, apprentices, and workers – contributes to the economy and future opportunities. Students, families, and Elders are all gatekeepers to understanding and developing the community.

Time has different interpretations in different cultures. Westerners (in varying degrees) tend to be rigid in imposing schedules and timelines that dictate our actions: when we get up, report for work, eat our meals, etc.. Those living closer to nature tend to follow nature’s lead and not impose a timeline upon nature: farmers know when to plant and harvest based on the weather; hunters and fishers know when to follow the seasons and weather events, from melting rivers to extended warm/cold periods. Following nature’s lead is not uncommon in Indigenous communities. An Inuit tour guide once told me, “Things happen when they happen. They take as long as they take. That is when I will be back.” An Elder from the Nisga’a Nation advised our project team that the start of Spring construction for their new facility would be late as “the oolichan are running early.” His forecast based on the Fall migration of the local smelt-like fish was correct. This is not mysticism, but a type of science different than the Western model, based on generational knowledge derived from close observation and a lifestyle integrated with nature. It was not possible to determine a fixed date for the opening of the Fall session of the Northwest Territories Legislature – on whose decisions our project depended – as many members were traveling over distance by land and water, likely on snowshoes or snowmobiles depending on the weather. They would arrive when they arrive.

The Indigenous approach to time can also involve a perspective spanning more than a lifetime. The Seventh Generation principle, developed by the Haudenosaunee Confederacy many centuries ago, is a philosophy that considers impacts of actions made today seven generations into the future, and to remember the seven generations who came before. This term has been accepted beyond Indigenous thinking for the advancement of sustainable practices (and products). Incorporating this into design may require significant changes of the design, location, size, materials, systems, use, maintenance, and nearly every feature of a facility.

What this means for the design process for a school is not to eliminate clocks or athletic timeclocks, but to build in more time than would otherwise be allocated for outreach, engagement, planning, and construction. People’s availability cannot be as structured and dictated as is common in urban settings. Major decisions frequently take longer; hearing all voices, deliberating silently, and arriving at consensus all take more time than many designers are used to. In my experience, it is not uncommon for meetings with Indigenous communities and individuals to have periods of silence; far more than with Westerners, silence is not to be avoided as it serves a purpose for contemplation and quiet deliberation. Voices will speak up when it is time.

Aesthetics in community buildings such as schools commonly integrate art and symbology from the local culture, including language and frequently family. These range from form and materials to vibrant colours and applied art, such as large logs or teepees. Indigenous signage may be in several languages, including special alphabets bearing little resemblance to mainstream characters.

Outdoor learning spaces are important for providing healthy natural learning spaces, for engaging with nature, and for performing types of experiential learning that are not suited for indoors. These range from simply inquiry to the very messy: horticulture, hunting, processing of game and fish, and even cooking. Many traditional foods require cooking over an open fire or smoking in a smokehouse or tent. All of these are part of curricula in multiple Indigenous-run schools.

Traditional food can also need a place for a feast, such as in a school commons or lunchroom. A kitchen needs to be suitable for community members, not just those trained to operate a professional commercial kitchen. Incorporating these traditional foods and methods support awareness and practice of healthy eating, community and cultural engagement, and career and technical training.

Connections to the outdoors can be structured to involve little travel to the outside. For just one example, locating suitable trees close to indoor learning spaces can provide habitat for birds. Students can design and building bird feeders, hang them in the trees, and study and paint or draw them through windows.

Outdoor learning may require nothing more from architects and designers than providing access and perhaps a place to sit or shelter from the sun, rain, or wind.

Integrating Nature into the Curriculum

The circle of life is taught and integral to Indigenous learning. It supports a holistic approach to life and learning and fosters development of empathy for other living creatures. One example is in this collection of images – although from different communities around the world, they tell a singular story: elders practicing their art of creating fishing implements; adults teaching youth to fish; places to gut and clean the fish; studying the fish and its anatomy in science labs; cleaning, cooking, and serving the fish to students (no preservatives such as formaldehyde are used). The fish is part of the culture, community, curriculum, and ceremony. Each of these requires spaces and places, each with specific physical characteristics. In many instances, equipment may be shared with others found in any school; some may require modifications to type of location; others, such as places to process hunted game, may require new types of facilities located on or even distant from the school grounds. Some may require working with local health departments and other agencies to help them understand the intent and importance of these unfamiliar elements.

Counseling and Sensory rooms are especially important for communities where an estimated 70% of student can be classified as special needs. Providing support for trauma-based care involves meeting and training spaces, places for students to power up, power down, and to heal. Methods and equipment may range from modern sensory spaces with special safety features to the traditional, such as a Cree swing.

Places for Ceremonies and Prayer are very important for healing. Re-establishing spiritual traditions amongst kids is a common programmatic request of Indigenous communities and Elders. Traditional healing practices may involve simple gathering in a circle, a place for smudging (with considerations for smoke), or a sweat lodge (a large room with special environmental features). Such community-based elements are not normally found in government funding models, and may require partnering or connection to other community buildings, such as described earlier for the new school at Frog Lake.

Room Configurations

Do we put the circle in our rectangular box, or do we shape our spaces to suit the activities and relationships? I had the honour and privilege of being part of the design team for The Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly Building in Yellowknife, northern Canada (above, left). It was the first legislature in Canada designed for Indigenous peoples where their interests, culture, ways of governance, and connections to the land and sky were enshrined in the design. Its main spaces are circular in form, generated by the seating arrangements of the elected officials. Unique in Canada to its three northern territories, each with numerically significant or dominant Indigenous populations, elected officials do not belong to a political party; there are no votes, no concepts of majority rule; decisions are by consensus. Debates take as long as they need to take. There is no “us versus them” approach to the proceedings or to the form. Seating is non-hierarchical, with special positioning reserved only for the presiding Speaker. Surrounding the chamber are interpreters’ booths for simultaneous translation into the 11 official languages, all but two being Indigenous. Above the booths is seating for the public, and above them is a continuous ring of skylights to capture the 360 degrees of summer daylight.

The circle is an important design feature in many Indigenous cultures, for reasons of symbolism, natural connections, and organization. The societies tend to be more communal as opposed to the western individualistic, and with less hierarchy. Tradition indicates this form of seating came from the campfire, where seating surrounded the source of heat and light. Artwork and placement is frequently organized around the healing circle with the four cardinal points, or quadrants, each infused with specific meaning, from directional to deeper symbolism.

For schools and learning environments, natural connections bring specific requirements and challenges. Outdoor activities mean different clothing and footwear. Space needs to be provided at entries and other areas for changing and storing. Space needs to be provided in the school schedule for this additional transition time (if there is a rigid schedule). A class trip may involve a 500 km/300 mile excursion to hunt a moose; after dressing it, the carcass is brought to the school for carving, distributing, and cooking and eating at school as well as at home. In the words of Plains Cree person, Darcy Lindberg, writing in Maclean’s in 2018:

“This is what Cree people describe as “four-bodied learning,” engaging with our physical, intellectual, spiritual and emotional selves. The practice ensures we are employing not just our intellectual selves, but relating to the ecological world around us with our full humanity. Practicing Cree law requires us to move beyond our intellectual aspects, as we must physically endure, spiritually connect and emotionally embrace our obligations to the moose’s life.”

Cultural Symbolism

Representing culture in architecture, design, and art is as old as cultures themselves. For Indigenous schools, there has been no less than a seismic shift in thinking. Before colonization, places of learning were largely the same as where one lived, worked, and worshipped - even those were frequently one and the same. With colonization came the residential boarding schools which resulted in imposition of Eurocentric culture, design, and symbolism. As those systems were dismantled, recognition and representation of Indigenous cultures started to become incorporated into design. More recently, the trend has been to incorporate actual Indigenous viewpoints and practices into the design from the start. The trends can be summarized:

Historic: Indigenous-only design

Colonizing: (early): Eurocentric design

Colonizing (later): Eurocentric interpretations of Indigenaety

Current/future: Indigenous-led design

The images below represent more recent examples of the current trends in architecture for Indigenous communities.

Incorporating cultural symbolism has been an important design approach for many Indigenous communities and an exciting challenge for many architects. Unfortunately, in multiple cases, the lack of authentic engagement with the stakeholders and communities has resulted in inappropriate imagery, forms, and references. The use of animal or bird shapes as inspiration for floor plans may only be recognized by those looking at drawings. One school in northern Alberta has a floor plan shaped like an eagle, although that bird has no relevance to the First Nation is serves. In others, the beauty of the teepee form has so captivated the designers and the distant government clients that it has been constructed in First nations with no history of this built form; in one such nation, the teepee is used only as a place of rest and healing for those with severe illness.

Natural Connections and Biophilia

These concepts and designs are important for everyone as they seek to provide healthier environments and reinforce and educate about our natural connections. They are especially critical for Indigenous culture, spirituality, and science. Biophilic design seeks to emulate nature in order to benefit from lower first costs, long term operational demands, and to have reduced or even positive impact on nature.

Providing physical connections to the outdoors can have significant functional and spatial impacts to the design of a school. Many indigenous communities are rural and may have fewer paved roads and pathways, or formal landscaping. They may have more airborne dust, mud, or even snow in the community and on the school grounds. For many such communities, they are further north and have long and very cold winters. People have different clothes for outdoors and for indoors. This is exacerbated when learning and other activities take place both indoors and outdoors. Extra space is needed for changing and safely storing one's outdoor footwear and clothing, such as in Kinput K-12 in Alaska below.

What I Can Do

As a designer, architect, planner, or anyone involved in working with Indigenous communities, there are many steps we can take to improve the design process, the projects, and the experiences of the communities they serve. Some of these are below.

A Restorative Model

Adopt and incorporate a model of practice, design, and learning that is rooted in restoration of relationships - past, present, and future - amongst people and nature.

Unemployment and poverty are rampant amongst Indigenous peoples across North America and much of the colonized world. Many of these cultures are seeing the start of a resurgence in rebuilding cultures and communities. At the same time, the entire world is becoming aware of the dire future we face as climate change begins to take hold, and as our centuries of devastation and polluting our air, water, land, forests, and oceans approach tipping points. It is becoming increasingly obvious to many that Indigenous perspectives and practices – the very ways of being – contain a wealth of knowledge and wisdom for all to learn from.

There is enormous opportunity – for Indigenous people to be supported in their learning, and to be supported by being engaged – hired (for pay) as teachers, mentors, facilitators, cultural translators, and more - to help all humanity learn a better way, better for our societies and better for our planet.

We have little to lose and potentially everything to gain.